Sloup–šošůvka Caves - history

PALEONTOLOGY

The Sloup-Šošůvka Caves represent a significant paleontological locality.

Freely accessible Pleistocene caves offered refuge and wintering for mammals that are now extinct. In particular, the cave bear. A large number of cave bear skeletal remains were well-preserved in the Sloup-Šošůvka Cave sediment.

In the last century paleontological research was carried out by such significant karst scientists as Dr. Jindřich Wankel and Dr. Martin Kříž. They were later followed by Jan Knies. The results of their work can be seen in the Moravian Museum in Brno or in the Natural History Museum (Naturhistorisches Museum) in Vienna where a large number of complete cave bear skeletons can be seen.

Over 300 skulls were excavated during Jindřich Wankel’s research alone. The corridor known as Gotická chodba is the richest deposit, however the skeletal remains can be found in the sediments of the whole complex of the Sloup-Šošůvka Caves.

Other Pleistocene fauna species which were discovered in Staré scaly include the cave lion, cave hyena, wolverine, wolf.

Current paleontological research in the Moravian Karst is being carried out by the Anthropos Institute of the Moravian Museum in Brno.

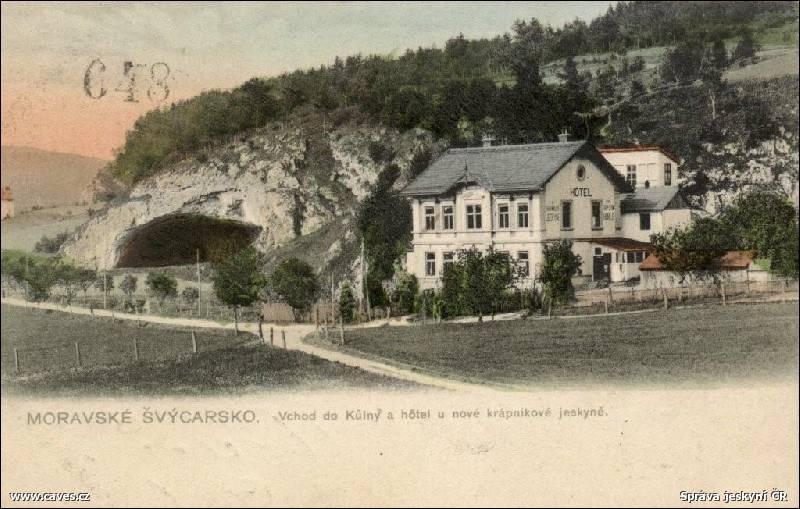

ARCHEOLOGY – THE KŮLNA CAVE

All over the world, the massive portals of cave entrances were used as prehistoric human settlements. There are several such caves in the Moravian Karst area.

The tunnel cave ruin called Kůlna is one of the most important. In the 18th century, extensive archaeological research was carried out by the scientist Dr. Martin Kříž. Up to 15 metres of cultural layers of sediment have been uncovered so far, thus a unique archaeological profile with human remains and the evidence of human activity in several important time periods came into being. The oldest archaeological evidence is comprised of stone tools with the estimated age of 120,000 years. The Kůlna Cave was then used by humans in different climatic periods.

Stone tools, animal bones and the skeletal remains of Neanderthal man were found in large quantities in the 50,000-year-old layer. They are parts of the upper jaw and a skull of a juvenile individual.

After the departure of the Neanderthals, the Kůlna Cave was settled several times by modern humans from the Upper Palaeolithic Era. They were mammoth hunters 22,000 years ago and reindeer and horse hunters between 13,000 and 10,000 years ago.

The Kůlna Cave was settled during the Bronze Age. The bronze artefacts dating back to the 9th–8th centuries BC were found in the sediments. The Kůlna Cave was partly damaged during World War II when it served as a factory for aircraft engines. After the war the archaeological research continued and valuable profiles were renewed.

The Kůlna Cave is one of the most important archaeological sites in the world.

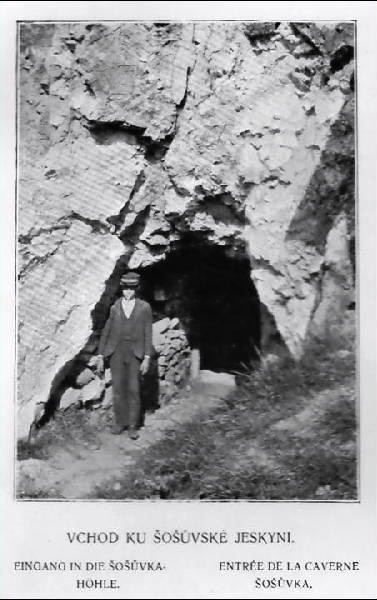

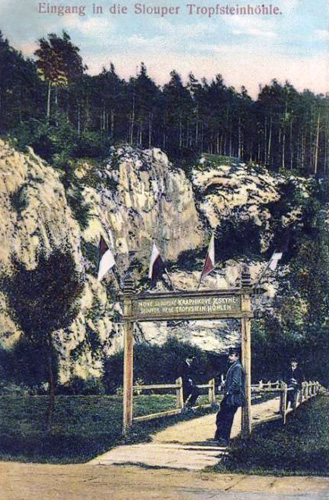

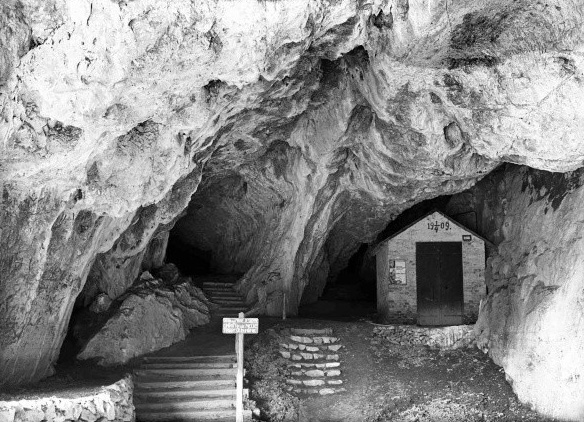

HISTORY OF THE SLOUP-ŠOŠŮVKA CAVES

"...When I was looking back while in this desolate and terrific rock maze of huge depth, I was attacked by such horror that all of my limbs shook and I was repenting of my sins with all of my heart. Amongst all the caverns I have ever seen, this is the ugliest one, as can be learned with horror by anyone wishing to search this place."

This is how Jan Antonín Nagel, a court mathematician and physician at the imperial court in Vienna, described the Sloup Caves in 1748. Nagel was entrusted to carry out the research and document the caves. At the same time he bravely descended to the lower levels of the cave through the Stupňovitá Chasm accompanied by local farmers. In addition to the precious manuscript, some unique drawings by Beduzzi, a painter who accompanied him, were preserved.

The first written mention of the Sloup-Šošůvka Caves dates back to 1669 and it was written by Johannes Ferdinandus Hertod of Todtenfeld. In the book called “Tartaro – Mastix Moraviae” (“The Underground Whip of Moravia”) he describes Moravian caves and the Sloup-Šošůvka Caves among others. His commentary was non-expert but is still priceless. For example, this is how he depicted the Kolmá Chasm:

"...Not very far from the boulder, there is a hollowness opening to the right, called the pit cave. If you throw a stone into it, you can hear it occasionally hitting the rock wall for as long as it normally takes you to say two Our Fathers and two Hail Marys. When the stone gets to the bottom and hits the water there, it hisses for several Our Fathers, just as if there were wasps flying around the mouth of the pit."

Hertod’s mention of Count Liechtenstein’s stone mason who descended to the lower levels through the Stupňovitá Chasm is also interesting"...fitted with a lantern and a pistol in order to give them a gunshot signal to pull him out. While holding the lamp mounted on a pole over the water, he saw giant trouts drawing near, which then overturned his lantern. Once he was pulled up back, he said that there were many more caves and other wonders down below - but then he suddenly died in the middle of telling the story."

Several explorers visited the Sloup-Šošůvka Caves after Hertod and Nagel. At Count Hugo Salma-Reifferscheidt’s bidding, K. Süsz drew the first map of the Sloup-Šošůvka Caves in 1800. There were several inaccuracies there, such as incorrect corridor directions or exaggerated values of length and depth. However, there are some correct topographic values and the Kůlna Cave according to Süsz is already reported as a part of the Sloup Caves. The visit of Emperor Franz I depicted by Jan Nepomuk Soukop in his guidebook “The Macocha Abyss and its Surroundings” in 1858 is noteworthy:

"...In 1804, Their Majesties the Emperor Franz I and Empress Teresia did not meet any trouble in descending to the bottom of the underground palace using the same way. A multitude of colourful lights then flooded the magical realm of Pluto."

In the second half of the 19th century, the paleontological research in the Sloup Caves was associated predominantly with Dr. Jindřich Wankel. He discovered many new parts of the cave and excavated and described a number of skeletal remains of Pleistocene fauna. Wankel’s closest colleague was Ing. Antonín Mládek, who among other things precisely mapped the Sloup Caves.

The year 1879 was significant for the discovery of Eliška's Cave, a cave into which the local resident Václav Sedlák fell while he was searching for cave bear teeth. An interesting method was used by Dr. Martin Kříž – when measuring the height of Eliška's Cave he released a balloon filled with air and tied to a string. Professor Karel Absolon started to participate actively in the activities relating to the Moravian Karst caves at the end of the last century. He continued with the research of his grandfather, Dr. Jindřich Wankel. He discovered some new premises in the Sloup Caves, became the assistant professor and worked with Josef Broušek during his exploration works in the Šošůvka Caves. The caves were gradually discovered during the years 1889–1914. The individual parts were interconnected step by step and made available to the public.

In the 20th century a number of expert and amateur speleologists, archaeologists, palaeontologists and other scientists from various fields contributed with their discoveries and research results to the understanding of this unique natural monument in the system of the Sloup-Šošůvka Caves.